On 7 October, 1922, Fukuoka City, Japan, could boast another addition to its growing population. That person was Hideo Yoshimura, and his name would ultimately become synonymous with superlative motorcycle performance.

But it would be another 32 years before that name was painted on billboard and hung above a small workshop in the backstreets of Tokyo.

As Japan began to militarise itself in the years leading up to WWII, Hideo was called into service and began his training as a navy pilot. But the training was cut short when Hideo and his parachute had a disagreement – which may have saved his life in the long run. So instead of flying planes during the war, Hideo was tasked with repairing them – a task he became very good at.

When the war ended and the atomic dust clouds settled, Japan was a country under occupation. The enterprising Hideo turned his prodigious mechanical talents to hotting up the plethora of Pommy bikes the US soldiers had acquired, and it wasn’t long before he was known as “God Hand” for his uncanny ability to manually make just about any engine part – from cams to carby jets – better. His personal enjoyment in hand-filing, grinding and improvising with crappy old tools was palpable and obvious to anyone who watched him at work.

In 1954, Hideo’s success at tweaking soldiers’ bikes enabled him to open Yoshimura Racing – a true and literal mum and dad concern. His wife, Naoe, made exhaust moulds and the finest lunchtime dumplings in Tokyo, and also became a master in hand-lapping valves. His daughter, Namiko, did the accounts and his son, Fujio, was his father’s shadow, learning at his feet and ultimately becoming a superb tuner and craftsman in his own right. Hideo was known as “Pops” around the shop – a nickname that was soon to resound around the racing world.

Pops was right at the forefront of the Japanese motorcycle boom that hit the USA in the early 70s. In 1971, he packed up and moved his family and his business to Los Angeles and was perfectly poised to surf the giant wave of Japanese superbikes like the Honda CB750 and Kawasaki Z1 that started to form. And in short order, Pops once again developed a reputation for making bikes go faster – though this time, he was working on bikes that were already fast to begin with.

As production road-racing began to blossom, Pops got his first taste of serious fame when Yvon Duhamel won an AMA production superbike race at Lagina Seca astride a Yoshimura-prepped Z1.

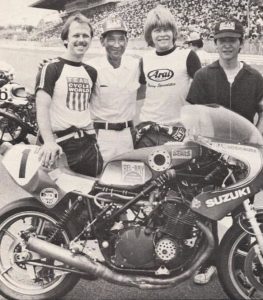

The rest, as they say, was history. Pops’ hideously quick and profoundly reliable Kawasakis dominated the AMA Superbike class, and in 1978, he got his hands on the first Suzuki GS750S. The Suzuki’s vastly improved chassis (over its competition), combined with Pops’ tuning sorcery soon saw a young and talented Wes Cooley winning championships in 1979 and 1980.

Suzukis began to sell themselves as a result of this racing glory and the factory acknowledged that Pops was an integral part of this sales success. And in very short order Yoshimura became the US racing arm of the Suzuki factory.

I started riding bikes around this time and my mates and I would literally salivate at the extremely rare Yoshimura parts that we would bump into from time to time. None of us could afford to buy the bits, but that didn’t stop us from stealing stickers, sticking them on our bikes and lying to vaguely interested parties how we each had a “Stage 3 Yoshi kit” on board. And while this statement may have worked in the case of us Suzuki riders, making those claims for Yamahas and Hondas did stretch the boundaries of credibility a touch.

Back in the States, Pops went from strength to strength on the racing scene and in 1979, Wes Cooley, Ron Pierce and Dave Emde made a clean sweep of the AMA Superbike podium. Yoshimura-prepped Suzukis won four AMA Superbike titles in a row from 1978 to 1981 – while Wes Cooley, Mike Baldwin and Pops somehow found time to also win the inaugural Suzuka Eight Hour endurance race.

Pops moved back to Japan in 1981.

He had carved the Yoshimura name into the stone of motorcycle consciousness, and wanted to oversee its Japanese operations in his twilight years.

He died of cancer on 29 March, 1995 – but his motorcycles continued to sweep all before them in the AMA, this time piloted by Australia’s own Mat Mladin, with six championships in seven years, and his teammate, Ben Spies, who took the AMA Superbike title in 2006 and 2007.

His legacy lives on in his son, Fujio, and I still have a Yoshimura sticker on my helmet. But I’ve stopped telling girls lies about his parts being on my bike.

by Boris Mihailovic