If you took a posse of seven really pissed off alley cats, taped knives to their paws, and threw them in a hessian potato sack, you still wouldn’t have seen a better fight than we saw at Assen in the MotoGP race on the weekend. It was one of the best bike races I’ve seen in years, and I’ve seen plenty. This was the stuff fans all over the world want to see, half a dozen or more guys banging bars, swapping paint, leaving front tyre rubber all over each others legs, and swapping positions like Cokeheads at a swingers party.

Assen’s like that. Always has been. It’s been producing tight races since Jesus was a snotty nosed kid riding a clapped-out unregistered Vespa through Jerusalem. This is mainly because the Assen TT circuit is a fast, flowing, balls out racetrack. A real race track. It really only has three corners you would consider “slow”, and that’s only relative to the rest of them, and two of those are placed one after the other. So for the rest of the way round, the boys are just on it. Tracks like that always produce great racing.

It doesn’t matter if he misses the podium. They love him regardless. And even the marshals look like vikings.

The wind helped this weekend too, as the headwinds down the fast back section of the circuit meant the rider in front was too busy punching a Grand Prix bike sized hole in the air to pull any sort of gap, and those behind in the slipstream could easily make ground. The other trait of this track that leads to close racing is that the fastest line into and out of a corner often leaves you susceptible to an overtake, so to protect your position you have to run slower lines. Going for the fastest lines leaves you vulnerable to someone sticking it up the inside under brakes, which just slows you down anyway. All of which makes for great racing.

Most of the corners have weird Dutch names, but you’ll only ever hear the commentators mention two of them, Ramshoek and De Strubben, although occasionally Stekkenwal gets a run too. That’s because they are the only names any English speaking commentators can pronounce, so they always hope the action takes place at those couple of spots. Sometimes they even use those names for other corners. Hey, it’s not like you know the difference anyway. It’s easy to see why they don’t use the other names, when some of them are Meeuwenmeer, Ruskenhoek, Duikersloot, and Geert Timmer Bocht. My personal favourite is Ossebroeken, named for that unfortunate incident in 1967 where a rider did actually have their arse broken. But I digress. This story isn’t about the weird Dutch and their strange language, or the fact they live in a usually cold country and think wooden shoes are a thing. I guess they did give us the story of the boy who stuck his finger in a dyke, so they can’t be all bad.

Zarco’s early season form has gone missing recently, but he wasn’t far away from the leaders.

There’s been plenty of commentary about how it was such a great battle for the win. It wasn’t really. Other than Marquez, they were all fighting for second. And they all knew it. Rossi admitted as much to me after the race. “He was faster than me, but he was faster than everyone.” Rossi was disappointed not to be on the podium, and likely would have been were it not for an exuberant passing attempt by Dovizioso that saw the pair having to settle for 4th and 5th instead of a likely 2nd and 3rd. That’s racing.

The podium was filled by Alex Rins, who described it as the hardest race of his life, and Maverick Vinales, who finally found some confidence and speed. The best part of this result is it should give both men a huge confidence boost to have done so well in such a hard fought battle, which will hopefully result in both of them spending more time at the pointy end in coming races.

Maverick found some speed, and some confidence.

So, back to Marquez. He just messed with them all weekend. He could run low 1.34s and even 1.33s seemingly at will, even on the hard Michelins, and he started doing it on Friday. He used one practice session to put in 22 laps over 3 runs on the same hard tyre, essentially doing a race simulation on it. Those 22 laps were littered with times in the low 1.34s. It was enough to tell everyone in the paddock that Marquez had the race pace on the hard tyre to win, and win well. Some of the others dropped into the low 1.34s and even 1.33s occasionally, but mostly with the stickier rubber fitted, and not with the consistency that Marquez was able to muster.

I asked Marc after qualifying if he planned to use the hard tyre and try and run that pace on race day, in an attempt to pull a Lorenzo and run away from them. “No Tug,” he smiled cheekily. “I’m going to win slow.”

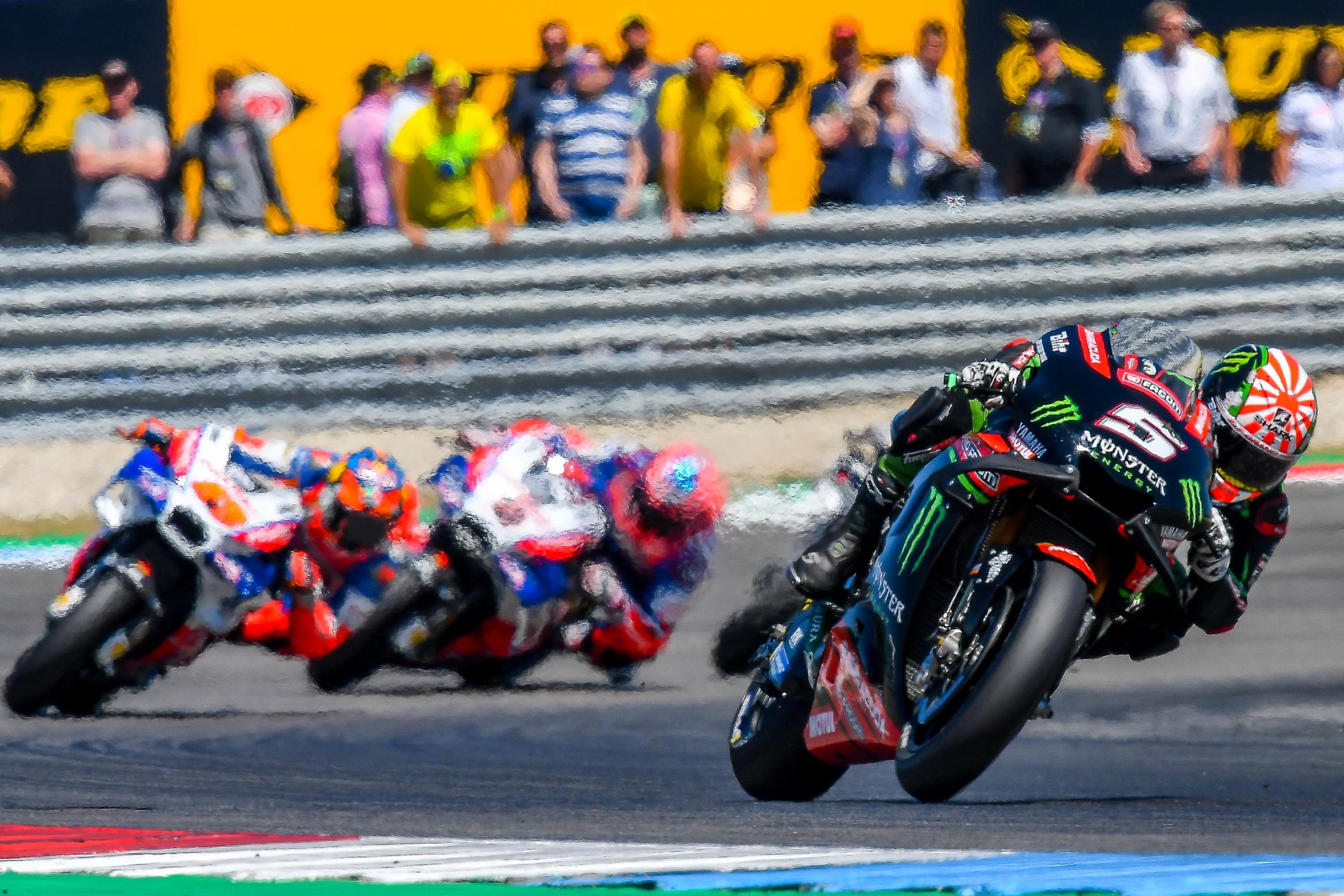

Marquez turns up the heat and starts to bug out, having finished toying with his prey.

“Bastard”, I thought. He was literally toying with them. You know a racer is at the peak of his powers when he has to manufacture his own fun. We’ve seen Rossi do it before, and now the Kid is doing the same thing.

Even in the morning warm up session on race day, Marquez ran the hard rear slick. He was also the only rider to drop into the 1.33s bracket. Take that, suckers. Catch me if you can.

So the scene was set. Everyone knew Marc had the pace to win, but everyone also assumed he was going to need the hard rear tyre to get to the end of the race, as he often does. That gave the rest of the field some kind of hope that they might be able to take advantage of some early grip if they went with the soft option tyres and maybe get out in front.

Imagine their surprise when Marc’s bike rolled out of the garage for the race with a soft rear tyre bolted in. Talk about a headfuck. Mind games used to be the specialty of the wily old Italian with the 46 on his bike, but the young buck is proving he’s pretty good at it too. In reality, the tyres Michelin provided for Assen didn’t actually have a lot of difference between the soft, medium, and hard compounds. So switching to the soft tyre wasn’t going to change things for Marquez to the same degree as it might have at some other tracks, but his point was still made loudly. I was faster than all of you on the hard tyre, so imagine how much faster than you I will be on the soft one.

So what was his plan? To use the soft tyre and his pole position to make a break and get away, then manage the tyre until the end? Given half a chance, he probably would have. But in truth, it was actually a master stroke of race strategy. He knew the strong winds and the nature of the track made it unlikely anyone would make a break early. Instead he expected them to form a pack and swap paint for the majority of the race, and run a pace closer to 1.35 than 1.34. Maybe slower. Like he said, win slow.

Rins declared it the toughest race of his life.

Under those conditions, and at that pace, Marquez knew he could make the soft tyre last the distance easily, and he would have the grip to check out at the end when the time was right. One thing for sure, when the rest of the field saw the soft tyre in his bike, they knew they were in serious trouble. At some point during the race, Marquez was going to pull the trigger, and when he did, they all knew nobody would be able to run with him. So they were just going to have to beat him up in the meantime and hope they caught a break.

Lorenzo had a go, barreling through from 10th on the grid to pretty much lead most of the first 12 laps. But he never really looked like getting away like he does when he’s right on form, and his Ducati was looking ponderous beneath him. He had a couple of big moments while leading, and after losing the lead he continued to have a few grip issues, one of which resulted in Rossi running fair up his arse. How the two of them stayed upright is a mystery befitting a Brian Cox documentary. I’m not even sure he could explain the physics behind that one.

Alex Rins pushed his Flying Blue Shovel through the field, and managed to not bury it in the gravel this week. He did almost bury Marquez in the gravel though, after a passing move on the Honda rider resulted in contact between them, with Marquez almost falling from his bike. His left foot was knocked off the peg, and his left hand was knocked off the bar in the impact, which also knocked his clutch lever around the bar, so he spent his next trip down the straight trying to pull it back into a useable position. Because holding onto a million horsepower MotoGP bike isn’t challenging enough already.

At this point Marquez has fallen off his motorcycle at 150km/h, after contact with Rins. He’s just casually climbing back on. Note you can just see his clutch lever, which is now underneath his handlebar.

After the race Marquez took responsibility for the contact with Rins, explaining that Rins had taken the inside line in the corner, so it was up to Marquez to stay out of his way. It was possibly a jibe at his opponents who often complain when he jams his Honda underneath them in corners. Rins did run a little wider than expected, but certainly nothing untoward or unreasonable, and Marquez had no problem with the move or the contact. And to prove it, he gave Rins a short back and sides as revenge when he caught back up to him. It was 1-1.

Vinales also muscled his way around and through some of his fellow riders. Again, nothing nasty, just good tough racing. Like the old days, before everyone got a little sooky.

Marquez worked his way to the front again, and with about 6 laps to go, decided to turn up the heat. His pit board showed him he had a gap of .2, which he knew was checked at the timing point for the 3rd sector, so by the time he got to his pit board the lead would have been more like .5 of a second. That meant he could now start to run faster ideal race lines without having to protect his position from the rider behind him, so he could start setting some sizzling laps and see if he could get away. And get away he did, winning by more than 2 seconds at the flag to finish a fantastic race.

You think he enjoyed that one?

The best thing to come out of all this is the level of competitiveness across the field is improving. Rins is fast and confident. Vinales has hit his straps. Lorenzo is back at the pointy end. It all bodes well for some great racing ahead. In fact less than 5 seconds covered the first 7 bikes. Tito Rabat was back in 16th, and even he was only 16 seconds behind Marquez. The bikes are more even than we’ve seen in years, and there are 10 or so riders capable of running near the front.

Their only problem, is what do they do about Marquez?