Australian motorcyclists reckon Wayne Gardner’s a top bloke because he was the first Aussie to win a World MotoGP Championship. They love that Casey Stoner took it the greatest riders in the world and beat them on a temperamental Ducati only he could ride.

But when they talk about Michael “Mick” Sydney Doohan their tone changes. It becomes reverent and filled with awe, like they’re discussing a deity whose prowess on a motorcycle transcended even the abnormal human abilities top-end motorcycle racers possess.

And they’re not wrong. It did.

The greatest motorcycle racer of them all, Giacomo Agostini, retired with 15 championships across all the classes. Valentino Rossi can claim nine world championships, seven of which are in the premiere class. They are the two greatest riders who have ever raced. The third is Mick Doohan and his five consecutive world titles.

But in many ways Mick Doohan transcends the two Italians. Because what Mick did, what he did it on, and how he did it after what happened to him simply beggars belief. It’s no wonder Johnny Depp wants to make a movie about him.

Motorcycle racing has always been a brutally cruel and dangerous sport. But never more so than in the Nineties, when the MotoGP soundtrack sounded like the deepest pit of some howling medieval hell.

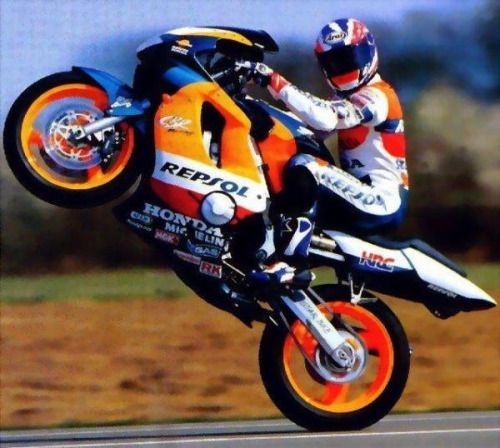

It was the time of the aptly-named Unrideables – screaming feral 500cc V-four two-strokes that weighed a mere 130kg, but developed (upon the instant) 200-plus horsepower, and stank like chemical warfare.

It was the time of racers being viciously high-sided into traction wards by 320km/h bikes that hated being raced by men who mostly hated racing them, but raced them anyway.

And it was the time of Mick Doohan.

Five of the eight Grand Prix titles in Australia belong to him. One belongs to Gardner and the other two are Stoner’s. From 1994 to 1998, there was only Mick Doohan. His mastery of the evil Honda NSR500 was astonishing and his dominance of MotoGP was total. In 137 starts, Doohan had 54 wins, 95 podiums and 58 pole positions. In those five years he reigned supreme, disappearing off the start and often leading by such a margin, he would slow down and cruise to victory in the latter stages of the race.

That he was able to race like that was astonishing. That he was able to ride at all after what happened in Assen is what makes Mick Doohan a legend.

Mick’s father died when Mick was twelve. It was a devastating blow, but it brought a realisation and a determination that would place him on track to greatness.

“Losing my father at an early age set me up to recognise that I’m the one out there doing it, and nobody’s going to give me a hand. And that’s where you realise if you are going to do it, you are going to do it by yourself.” And so he did.

His path to MotoGP, at the age of 18 (that’s about 13 years too late in today’s terms), began when he was offered a one-off ride in the Australian Superbike Championship, after a promising season of belting around on 250cc production bikes. Mick came fifth. This led to him throwing a leg over a full factory Yamaha and making a name for himself on the 1988 World Superbike stage with multiple victories, backed up with two first places in the Australian round.

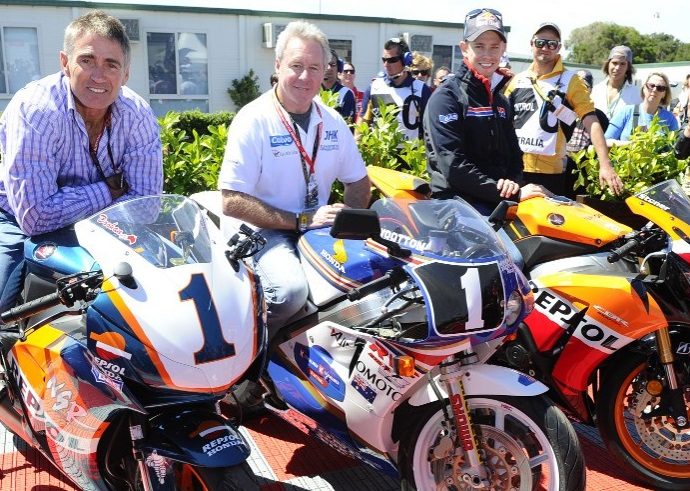

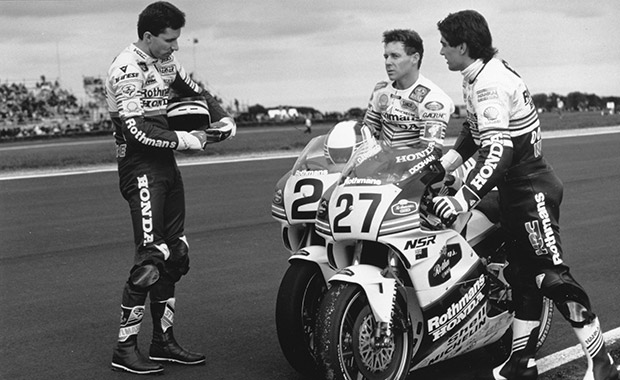

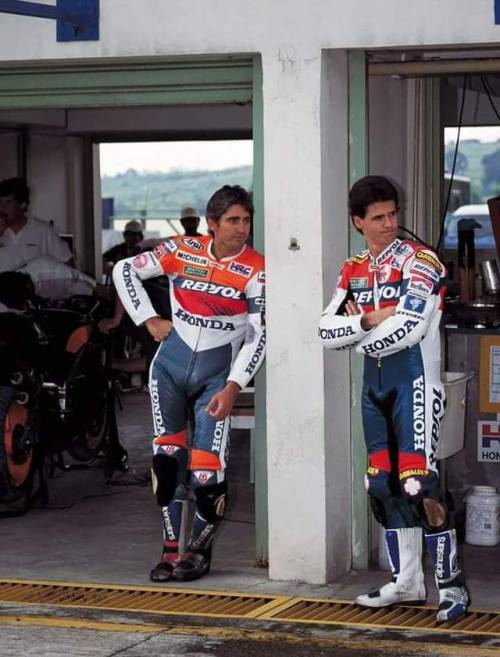

MotoGP was clearly next. Yamaha wanted to keep him, but Mick eventually signed with Honda and was partnered with fellow Aussie and world champion, Wayne Gardner, in the factory Rothman’s Honda team.

It had taken Mick just 18 months from riding 250cc production bikes on Australian goat-tracks to climbing onto a fully-loaded 500cc MotoGP factory bike.

But he must have been wondering what he’d signed up for. The Honda NSR500 was a wicked and savage brute of a bike, and had been resolutely trying to murder Gardner the entire previous season. In 1988, Wayne had spent more time flying through the air than Qantas, and Mick soon joined him up there in 1989.

He managed a third at the insanely fast Hockenheim circuit behind Eddie Lawson and Wayne Rainey, but a crash at the Suzuka Eight-Hour (he was leading) cost him his little finger. His digit was re-attached, he sat out three races and saddled up for the final round in Brazil where he came fourth.

Battered but unbowed, Doohan returned with his team-mate Gardner in 1990. He crashed some, but started to deliver top-five finishes, before overwhelming the world champion Wayne Rainey in Budapest for his first MotoGP victory.

Gardner, Australia’s only contender against the awesome talents of Rainey and Schwantz (who had their own fabled hate-fest going), was suddenly in red-hot battle for first place against his own team-mate, who pushed him relentlessly at the final race in Phillip Island, finishing just 0.8 of a second behind him.

Never mates and polar opposites, Mick was an entirely different kind of animal to Wayne, as chief mechanic Jeremy Burgess recalled.

“Wayne needed to be pumped up. You would have to go and tell him that ‘You can beat those guys. You beat them last week. You can do it.

“If you said anything like that to Mick Doohan, he’d look down at you, and say, ‘What, don’t you think I can do it?’

“Mick had confidence, and he crushed his opposition before he even got on the bike. I mean, he didn’t talk to them in the paddock. He was awesome in that respect.”

The 1991 world title was obviously possible and Doohan started with a bang, leading the championship as they arrived in Assen. But the malevolent NSR had other plans. He lost the front-end chasing Schwantz and Rainey, and hit a tyre wall like a rocket-propelled melon. He wasn’t badly hurt and managed second in the championship that year.

Then came 1992 and everything changed. Honda realised it needed to do something about its serial-killer NSR and changed the firing configuration of the cylinders. Dubbed the ‘Big Bang’ engine, it was down a little on power, but far more rideable.

But not for Wayne, who had a career-ending crash in the opening race and left Mick to win that one and the next three as well. In the first seven races of that season, Mick won five and placed second twice.

The championship looked like a done deal. Until Assen, when the NSR really made an effort to end him. It high-sided Mick at 160km/h during practice, landed upon him and ground his right leg into meaty jam.

“The bike rode in on top of me,” Mick later recalled. “I spun myself out from underneath it, or tried to, and everything spun except for my leg.”

The break itself wasn’t bad, but when Compartment Syndrome and gangrene set in, surgeons pushed for an amputation.

“I remember seeing all these black spots on my leg, not really knowing what it was. It wasn’t until the doctors started scraping at these black patches; they just kept going until there was just a big hollow hole about the size of my fist all around my ankle and the same on top of my forefoot.

“This is where I’m thinking, ‘perhaps I might lose this leg, and the championship might actually not be possible’.”

Only the legendary Doctor Claudio Costa disagreed and offered a solution.

Only the legendary Doctor Claudio Costa disagreed and offered a solution.

“He said it’s a bit barbaric, and it hasn’t really been done for 20-odd years, but because the circulation was bad in my right leg, he suggested we could steal some skin and flesh from the other leg and feed the blood supply from that left leg into the right leg.”

So Mick had his legs sewn together for two weeks. Eight weeks later, he presented himself at Phillip Island ready to race. He had to hide his crutches from Race Control, hobbled onto his bike, and after a few laps saw he had ground away his little toe because he couldn’t move his foot off the peg. It was not his year.

He was back in 1993 and took four pole positions and a victory at Mugello, but it was not his year either. His bike had been fitted with a thumb-operated rear brake and Mick was once again threatening the front-runners, but ran wide at Laguna Seca, crashed and broke his collarbone. He couldn’t saddle up for the final round.

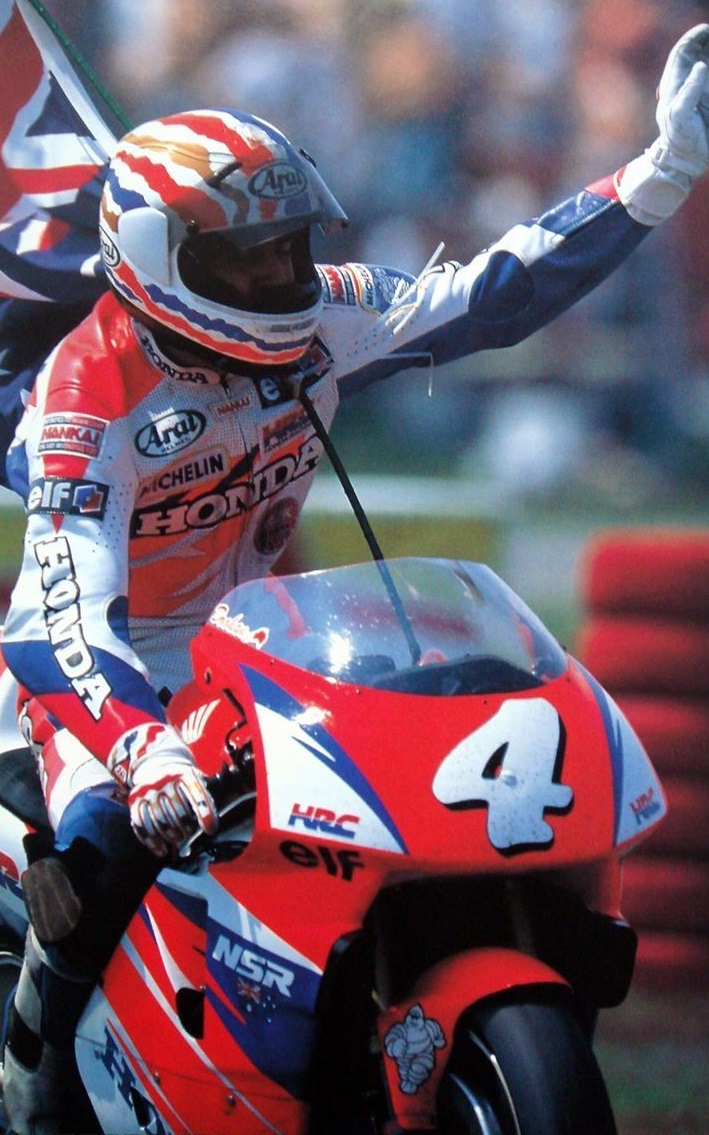

Then in 1994, the Age of Doohan began, and its like will never be seen again. The next five years and titles belonged exclusively to him. Certainly, there was the odd epic battle with Biaggi, Okada and Criville, but in the end, it was a champagne-washed Mick who raised the World Championship trophy over his head.

He even went back to the screaming death-hearted NSR of old in 1997, because he knew the sight of him frying his back tyre out of corners was like beating his rivals’ spirits with a claw-hammer. And beat them he did, winning 12 out of 15 races (with 12 consecutive pole positions) and finishing second in the other three.

His final title was decided in 1998 at Phillip Island in front of the largest crowd to have ever attended the circuit until that time.

The following year, the tightrope he’d ridden for so long and so well finally snapped. He highsided at more than 200km/h during qualifying at Jerez, and flew straight into the exposed Armco.

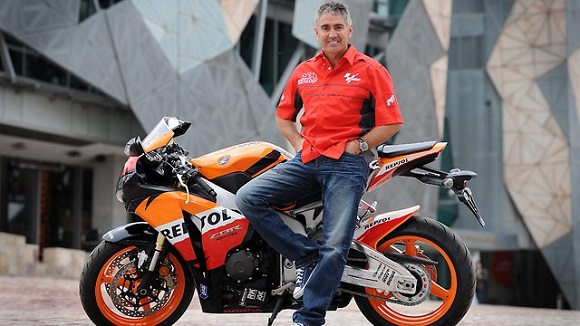

It was over. He’d broken his wrist, his collarbone, his foot, his ribs and his hand, and bruised everything from his lungs to his spleen. There was no coming back this time and Mick retired a few months later, facing years of ongoing surgery.

But it’s impossible for a racer like this to just fade away. He was appointed General Manager of Honda Racing Corporation in 2000 and was instrumental in guiding Valentino Rossi to his first two MotoGP championships. He did this by detuning the psychotic NSR Honda to a mere 168-horsepower, because Rossi just wasn’t able to cope with the 200-plus Mick Doohan version.

THE THUMB BRAKE

As a result of his right leg resembling like a rotting sausage, Doohan was unable to effectively use the back brake on his racing bike. So Honda designed and fitted a thumb-operated unit to his handlebar, and Mick went on to win five world championships. Unable to come to terms with just how fast he was, some of his competitors put it down to his thumb brake and demanded the same set-up be put on their bikes. They promptly went backwards at an even faster rate. Mick’s chief mechanic Jeremy Burgess still chuckles about it.

As a result of his right leg resembling like a rotting sausage, Doohan was unable to effectively use the back brake on his racing bike. So Honda designed and fitted a thumb-operated unit to his handlebar, and Mick went on to win five world championships. Unable to come to terms with just how fast he was, some of his competitors put it down to his thumb brake and demanded the same set-up be put on their bikes. They promptly went backwards at an even faster rate. Mick’s chief mechanic Jeremy Burgess still chuckles about it.

“It was built out of necessity, and it achieved exactly what we wanted. And we were flattered by the fact that people copied us. But as Mick said, ‘Geez, if I had a good foot, I wouldn’t be putting this on the bike’. But everybody was saying how wonderful it was, and that’s why Mick’s winning races.”

The thumb brake has resurfaced in recent times, with a few of the top runners giving it a go to see if it would give them an edge. Jorge Lorenzo has tried it, as has Tom Sykes over in World Superbikes. But it’s become a permanent fixture on MotoGP’s Andrea Dovizioso’s Ducati. It hasn’t helped Andrea win anything, but it’s probably stopped the Ducati from trying to kill him with monotonous regularity.

BY BORIS MIHAILOVIC